A little while ago, I saw a post on LinkedIn that essentially said “Don’t hire a finance pro to build your model! Do this instead!”. “This” turned out to be color coding your tabs…

Ground Floor Financial Modeling

Here’s the thing. If you don’t have a background in finance or accounting (preferably both!), then you’re probably going to miss something when putting together your financial model. Early on, that’s likely not going to be a dealbreaker for investors. Founders are expected to be jacks of all trades with an ace core competency. Maybe you’re a brilliant coder. Maybe you could sell Dodger hats in San Francisco. Maybe your rolodex includes two ex-presidents and LeBron James.

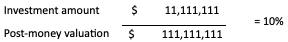

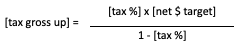

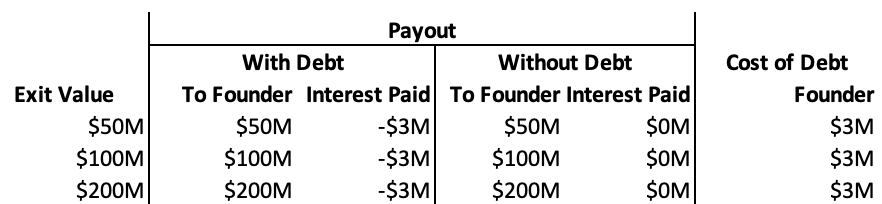

Wherever your strength lies, you’ll still be expected to know how to hire, understand what an attractive app/website looks like, avoid breaking any employment, trade or tax laws, have a basic understanding of cap table mechanics and, yes, build a rudimentary financial model in Gsheets or Excel. So a formula error at the seed stage probably isn’t going to torpedo a deal.

Seed stage models are usually trying to answer a primary question, which can vary depending on the business. For a novel technology, the question might be “how much money do you need to validate the core technology?” For a SaaS business, it might be “how much money do you need to build the MVP?” For a consumer hardware business, it might be “do the unit economics work?” If you’ve been thoughtful about answering the primary question that the model is trying to answer, you’re probably in good shape.

Operational Financial Modeling

Once you’ve obtained seed funding, have hired a few folks, and are getting ready to launch your product, operational finance and accounting becomes much more important. So let’s put aside for a moment the use case of sharing your model with prospective investors (another debatable topic). Let’s focus on generating the data you need to run your business.

As I’ve stated in an earlier blog post, the number 1 rule for any business is: don’t die. So if your cash balance isn’t your most important metric today, how do you ensure that it doesn’t suddenly become your most important metric tomorrow? You do that with a rock solid financial model.

Here are a number of pitfalls that I commonly see in founder-prepared financial models (let’s call these “founder models”) when working with new clients:

Where’s the balance sheet? In most of the founder models that I see, there is no balance sheet. There is usually a rudimentary calculation for cash, based on EBITDA or net income, but no other assets, liabilities or equity. Why is that a problem? Because that’s usually not how cash works…

If your business relies on working capital such as AR, inventory, accounts payable and deferred revenue in any sort of meaningful way, fluctuations in working capital could have a drastic effect on your cash balance.

Cash is the plug on the balance sheet. This is counterintuitive, but the best way to forecast cash is to nail down the forecasting of all of the other balance sheet accounts and then let the cash number fall out as a plug to force the balance sheet to balance.

Spreadsheet equivalent of spaghetti code - You started building a model for your company, but then your strategy shifted. And then it shifted again. You probably should have gone back to the foundation of your model to efficiently portray your current approach, but that seemed like a lot of work so you built on top of what you had before. Now it’s a headache to trace your formulas from one tab to the next.

Revenue recognition - If you have multi-month contracts, or staggered performance obligations with your customers, you likely need to think carefully about how you’re recognizing your revenue for two reasons:

Cash - I keep coming back to cash, because it’s that important. In some cases, the way you are recognizing revenue in your model could have a major effect on your cash forecast. And if you get it wrong… bad things could happen.

Audit adjustments - Most of the time, your auditors will want to make some minor tweaks to revenue recognition during a first time audit. So most of the time, investors don’t mind some adjustments to what you had previously reported. Every once in a while though, I see a founder model that has some wildly incorrect assumptions about rev rec that could have major implications on the health and growth trajectory of the company. In these cases, investors will care.

Bad accounting - Please see my previous blog post about this. An erroneous balance sheet, poor consolidation tactics, and gross margin inconsistency are a handful of items that both look bad from an accounting perspective and can materially throw off your forecast.

Inelegant/risky formulas - If(sumifs(if(min(max(if(vlookup(.... If this looks familiar to you, call me.

Hardcoded links - Linking between tabs with a hardcoded cell (i.e. “=F37”) makes models easier to trace, but also more fragile. If you change a column or row structure in your model, it could throw off your model on other tabs.

Error checks - Most founder models don’t have simple checks to ensure that the balance sheet balances (if there is a BS), retained earnings rolls forward, net income is consistent from tab to tab, the cash flow statement matches the cash balance on the balance sheet, etc. Without these checks, it’s more likely that there’s an embarrassing mistake lurking somewhere in the model.

When thinking about these pitfalls, there’s a huge difference between “oops! Formula error!” and “oops! Where did all our money go?!”. So once companies reach the point where they’ve graduated from “ground floor modeling” to “operational modeling”, it’s probably time to consult with a finance pro.